Years ago, I realized that the beautiful thing about the way the Marines teach trust is we don’t actually trust each other so much as we trust our ability to inventory our teammates. What we trust is our own assessment of our peers. Francis Fukuyama wrote a sociological treatise in which he posited that the most successful societies were built on Trust. And the Marines are one of the most successful organizations because of our Trust. It’s just not quite the kind of trust you might imagine.

I’ll give you an example.

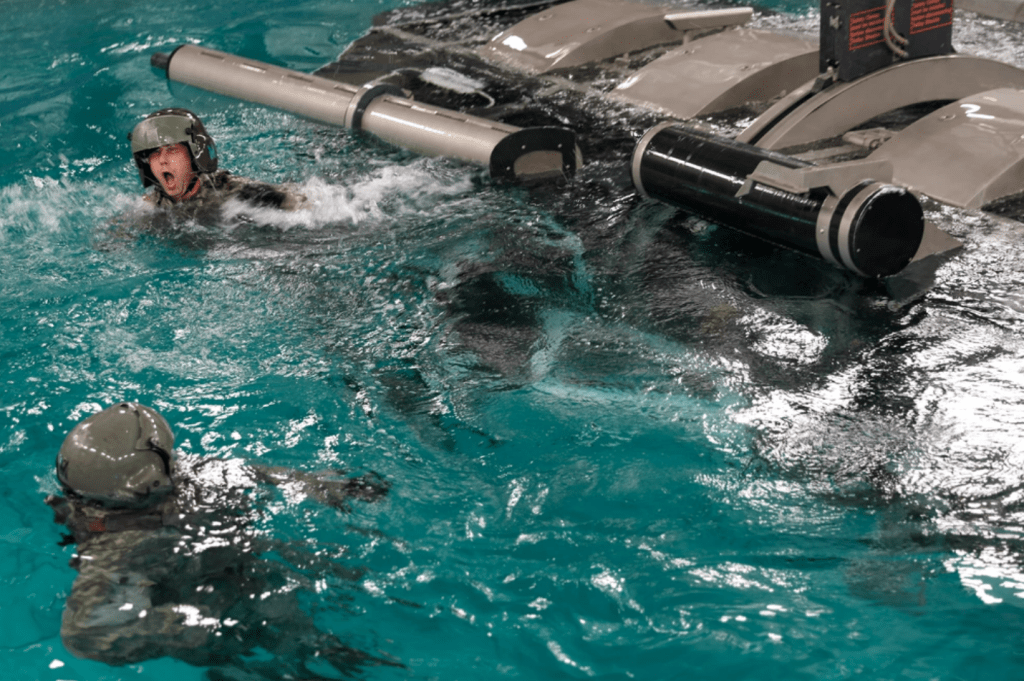

When I joined the Marines, I couldn’t swim. I nearly failed out of boot camp because I couldn’t swim. After passing boot camp with the lowest level possible, I tried repeatedly to get backseat jet qualified. The aviation swim qual is brutal. I failed repeatedly and they had to pull me off the bottom of the pool with that long hooked thing after I started sinking with my aviation gear and boots on. I went through the dunker chamber 4x and on the 3rd try with darkened goggles, I couldn’t find my belt to release it. That’s because I didn’t follow orders. I should have put my hand on the far side of my hip and followed the belt across to get to the release. But being freaked out by being upside down underwater in a tin can, when I didn’t have blackened goggles, I had just looked down and grabbed as fast as I could. Once I had blackened goggles and I couldn’t see the buckle, I freaked out. It took me a few seconds to release the buckle and then I followed the belt and arrived at the buckle but I had exceeded the time the navy divers were allowed to allow us to stay in the can which is counted in seconds.

It felt like someone punched me in the chest. A hand of God grabbed my flight suit and threw me on the surface of the pool beside the ladder going out of the pool. Then I had to go back in again. This time, darkened goggles, but only out the crew door, not just any door.

Later I took advantage of my assignment at MCRD San Diego and went to the pool every week when the recruit depot swim instructors made themselves available to the active duty personnel there to improve our swim skills. I upgraded from Level 4 to WSQ Water Safety Qualified, the highest level before WTI Water Training Instructor. I took and failed the WTI entrance exam repeatedly just like I had taken and failed the backseat jet water qualification.

How could I face my fear of water? Because I knew that water instructor Marines would sooner die than allow a Marine in their charge to die on their watch. That’s not to say one of them wasn’t alcoholic or even in rare circumstances addicted to cocaine. That’s not to say they weren’t the product of a domestic violent upbringing and weren’t practicing what they learned as kids now that they had families. That’s not to say one of them wasn’t sexually abused as a child and inclined to continue the tradition. That’s just to say I had zero doubt they would pull me off the bottom of the pool. I’m not saying all Marines have some substance abuse or other issue. I’m just saying it doesn’t matter with regard to trust. Because we trust each other based on our evaluation of each person’s character and skillset.

Later while serving in the State Department, a colleague complained about me inviting the secret service on our review of the sites we were responsible for during the 1st Lady’s visit to Busan. I responded to her (rather sarcastically) that law enforcement men like them had a higher probability of domestic violence and alcoholism, but I didn’t care if the 2 men beat their wives, kids and dogs when they went home, for the next 2 weeks, they were surgically attached to our hips.

So it was with Marines. They taught me to understand when and why I could and should trust my teammates. Every person I met, I was taught to do a personal inventory. In the Marines, I did it via an initial interview, but my State Department colleagues protested the probing questions about upbringing and hometown, etc., so I began to do it more stealthily, but I never stopped. To this day, I try to take inventory of everyone around me. I want to know each of my colleagues strengths and weaknesses and to rely on their areas of strength and reinforce or redirect tasks that don’t play to their strengths.